Chile’s Struggle for Democracy

Documenting political movements in Santiago, Chile after the “Estallido Social” mass uprisings.

Photographed by Dylan Manshack (2022)

Part One: Street Protests Resume Post-COVID

The 2019 “Estallido Social” mass protests in Chile were initially triggered by increase in the rate of the Santiago public transportation system, however, the high cost of living in Chile had been making the country increasingly unaffordable for working class Chileans. As a result, protests quickly became about low pensions, high costs for health treatment, and a general rejection of the dominating political class in Chile, including the country’s entire Constitution that was created under the Pinochet dictatorship.

On the night of Friday, October 18, 2019 the protests began to spread throughout the country with millions participating in the social unrest. This caused President Piñera to declare a state of emergency and implement a curfew the following day. The protests continued until the COVID-19 pandemic reduced the scale of protests following strict social distancing and quarantines imposed by the government.

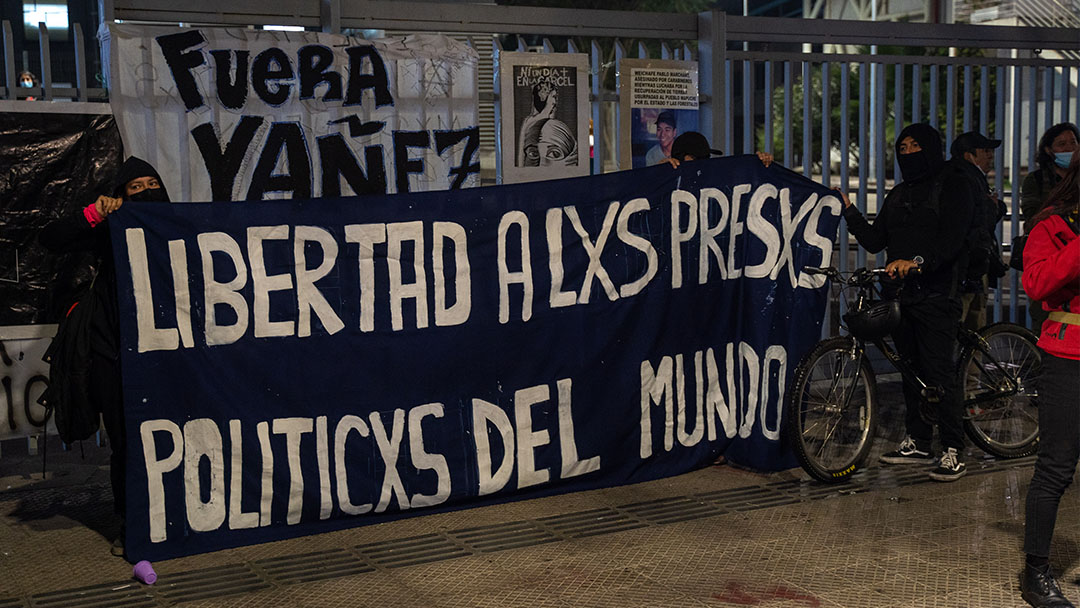

Since pandemic restrictions have ended, some Chileans return to the street each Friday night to commemorate the beginning of the Estallido Social and to protest for the release of protestors arrested during the unrest two years ago. I captured the following photos on one such night in March 2022 after hearing protest chants and seeing street fires from my apartment balcony.

Officers from the Carabineros de Chile, Chile’s national police force, stand beside a water truck as it sprays the protestors further down the street.

Protestors throw rocks at the police truck as it sprays water on the crowd and extinguishes street fires.

A volunteer medic from “Brigada Dignidad” monitors the street demonstrations.

A protestor is caped in the “Flag of the Mapuches”– a symbol of the indigenous peoples of Chile, the Mapuche Nation.

A banner reads “Liberate the Prisoners of the World” in a reference to the protestors who are still in jail two years after the Estallido Social.

A hooded protestor holds a banner for Cristián Valdebenito who was killed after being hit in the head by a tear gas canister fired by agents of the Carabinero (military police) during a protest in Plaza Italia (renamed Plaza Dignidad).

Part Two: Thousands march for a new constitution on May Day

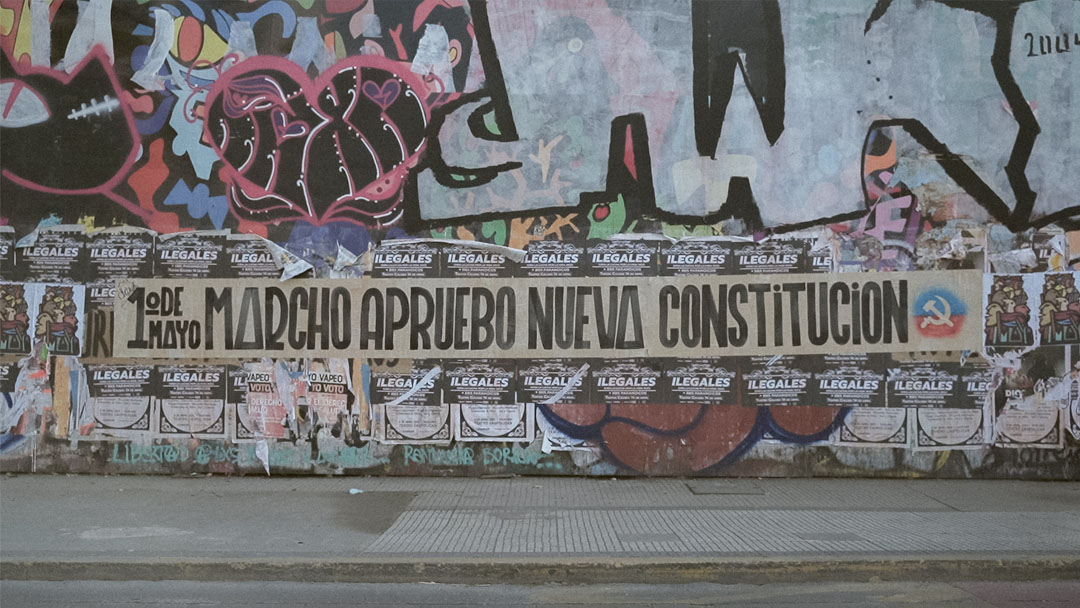

On May 1, 2022 thousands of Chileans took to the streets of Santiago to celebrate International Workers Day, or May Day. Much of the demonstrations focused on demanding a new constitution for Chile.

The demands for a new Constitution in Chile are not new, though the Estallido Social did lend the movement renewed support. The existing Constitution was created under the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet and, as a consequence, many Chileans demanded a new Constitution to be drawn up democratically to protect the democratic rights of Chileans. Political pressure after the Estallido resulted in the formation of a Constitutional Convention to carry out this very task.

In the following photos, you will see some of the people and organizations demonstrating a new Constitution for Chile. These photos are set about four months before the constitutional referendum vote to approve the new constitution which ultimately failed to gain majority support in September 2022.

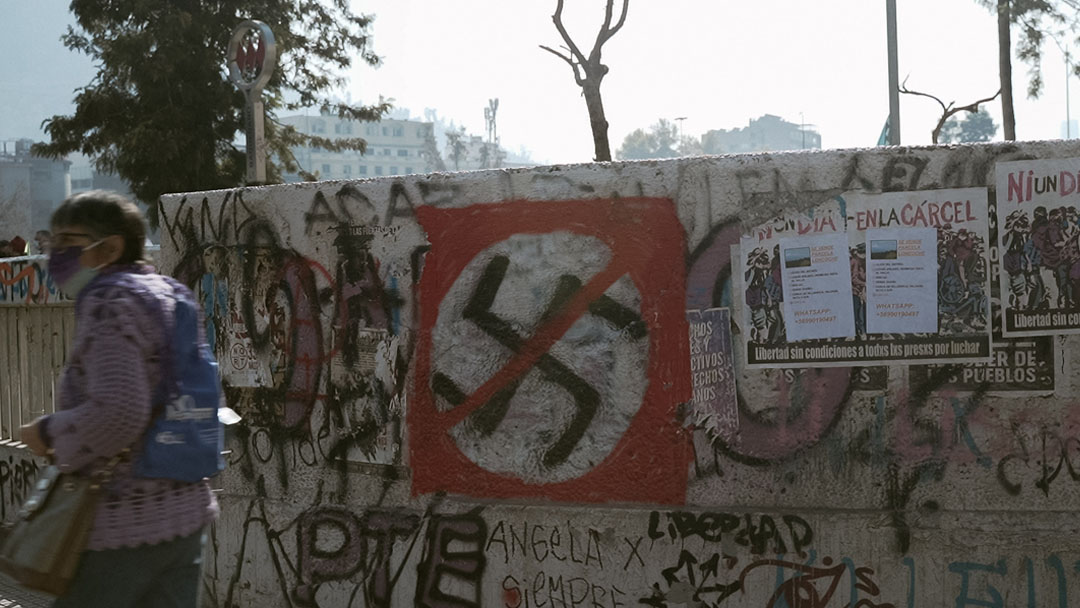

A swastika is painted over in Plaza Dignidad to condemn the far-right that has seen a resurgence in Chile since right-wing candidate José Kast ran a popular campaign against President Gabriel Boric.

A union worker from the Sindicato Interempresas Líder de Trabajadores del Holding Walmart (a union of Walmart workers in Chile) beats a drum to begin the May Day march.

A demonstrator holds a sign of Salvador Allende, the former president of Chile who was killed in the US-backed coup that brought the Pinochet dictatorship into power. It says “I’ll always be with you” as Allende was (and still is) incredibly popular among the masses in Chile.

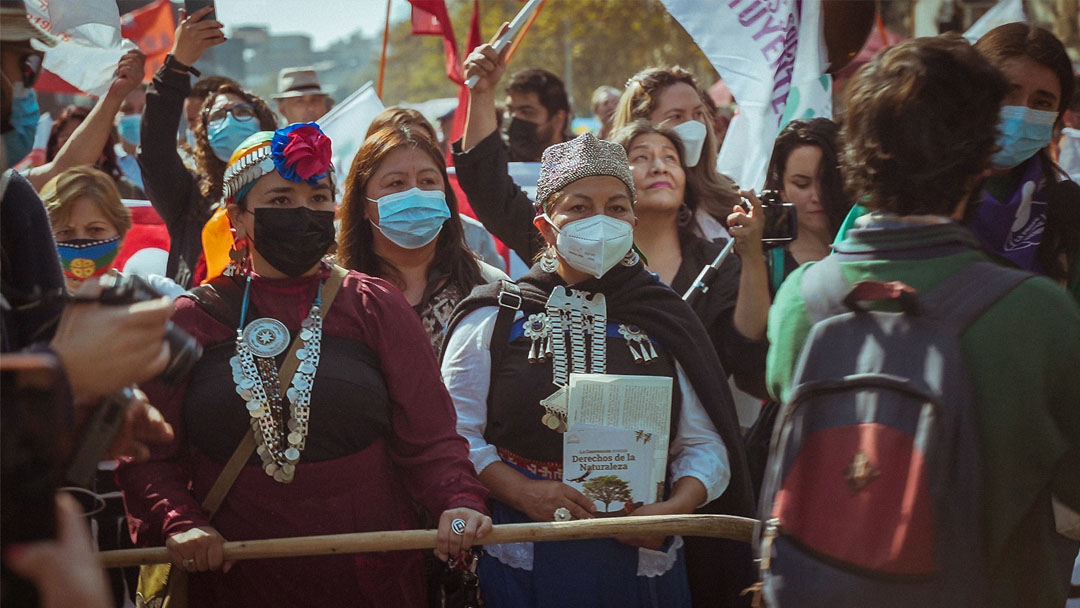

Elisa Loncón (middle, holding papers) is seen marching among the demonstrators on May Day. Loncón is a Mapuche woman and the first person to preside over the Constitutional Convention to rewrite the Chilean Constitution. It is significant as she is part of the largest indigenous community in a country where native people have had little say in the running of the country and are not even mentioned in the existing Constitution as Pinochet’s regime sought to erase the history and culture of the Mapuche entirely during his reign.

A May Day street banner advocates for the approval of a new Constitution.

Mayor of Recoleta, Daniel Jadue, speaks with constitutes at the May Day march. Jadue has become internationally recognized for his successful social programs implemented in the Recoleta commune. Jadue created the first “People’s Pharmacy” in the country, allowing drug prices to fall by 30% to 50% (three companies have traditionally exercised an oligopoly in this market in Chile) and since then 150 municipalities in Chile have adopted similar systems. Jadue also ran against President Boric in the 2021 Apruebo Dignidad presidential primaries and lost despite leading in the polls.

A labor activist leads a broad coalition of demonstrators in chants before the main events of the day begin at the May Day stage hosted by CUT, the country’s main trade union federation.

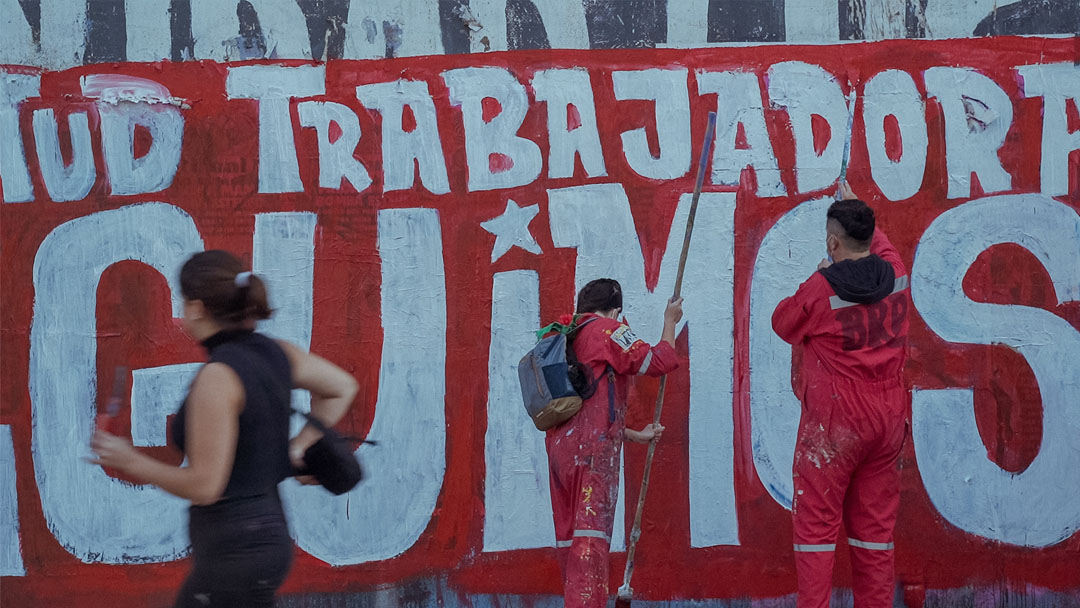

Members of the Brigada Ramona Parra (BRP), one of Latin America’s most well-known and resilient artistic collectives, paint a May Day street mural to advocate for the approval of the new constitution.

Part Three: The city as a medium of protest

mess

Street art has historically been an important tool to demonstrate against the oppression of the Chilean people. During the Pinochet dictatorship, it was illegal to demonstrate against the government so artists would secretly paint the streets with messages of liberation for the Chilean masses to protest the violent oppression by the Pinochet regime. However, if the muralists were caught they would be executed by the dictatorship. After the Estallido Social, there has been a huge resurgence of revolutionary street art that covers all parts of the city.

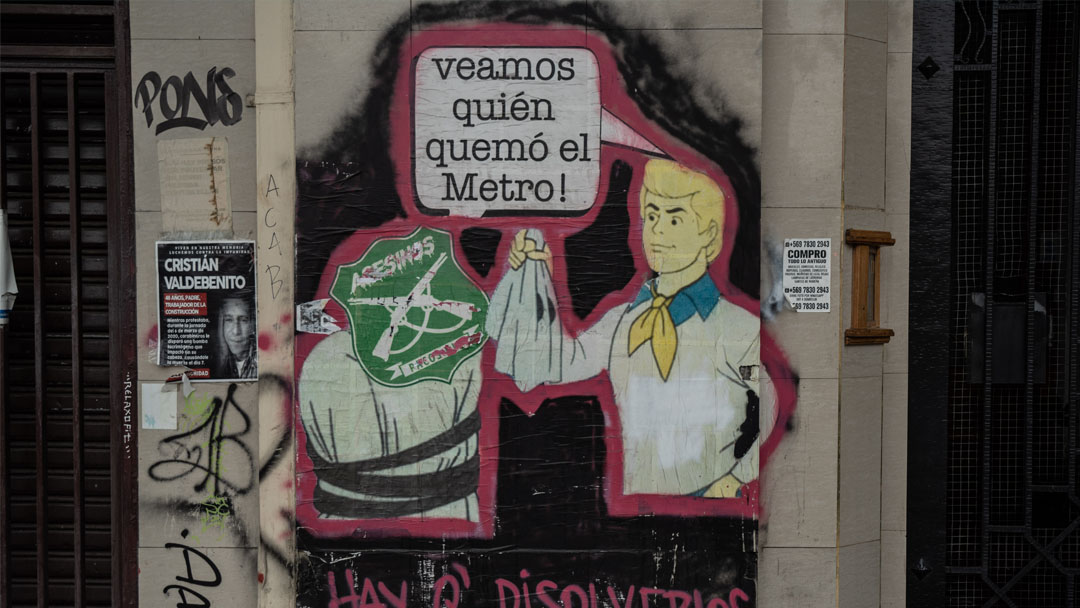

The first photo in this series depicts a former metro station in Plaza Baquedano that was shut down after it was set on fire during the Estallido Social of 2019. While there is no confirmation of who set the fire, police blame the fire on the protestors while many protestors believe the fire to have been set by the police themselves. Consequently, the metro space was turned into a memorial by protestors to remember those who had been killed by the police during demonstrations against the Chilean government or during other incidents of police brutality. The memorial sits in a plaza that was formerly named “Plaza Italia” before protesters renamed it to “Plaza Dignidad” as a nod to the dignity they seek to bring back to their democracy through radical social change.

A mural painted alongside the Mapocho River reads “The Revolution is Possible” with a flag for the “Grupo de Amigos Personales” which were the armed guard of the Socialist Party of Chile in the 70’s for the protection of Salvador Allende before the infamous 1973 Chilean coup d’état.

A mural in the metro memorial depicts three women above the words “Origin”, “Liberty”, and “Love”.

“Negro Matapacos” sits in the middle of the memorial with a Women Power fist on its bandana. Negro Matapacos translates to “Black Cop-Killer” and represents a stray black dog that often wore a bandana and participated in the Estallido Social protests against the police in 2019. He became a symbol of resistance to police brutality and is a common fixture in murals around the city.

A mural playing on the unmasking of villains in the Scooby-Doo TV series reads “Let’s see who burned the Metro!”. Under the mask is the symbol of the Carabineros de Chile (military police) with the word “asesinos” on the emblem meaning “killers”. This mural is directly across from the burned metro station-turned-memorial.

What was formerly statue of Chilean military general and president, Manuel Baquedano, has now become a space for protest art demanding dignity, truth, justice, and liberty. The statue of Baquedano on horseback was removed after defacement during the Estallido Social.

An intricate mural depicts a banner that reads “The World is Going to End” with other lyrics from the song “El Mundo” by Molotov. In the mural the world is held up by imagery of war, monopoly capitalism, white supremacy, and colonialism.

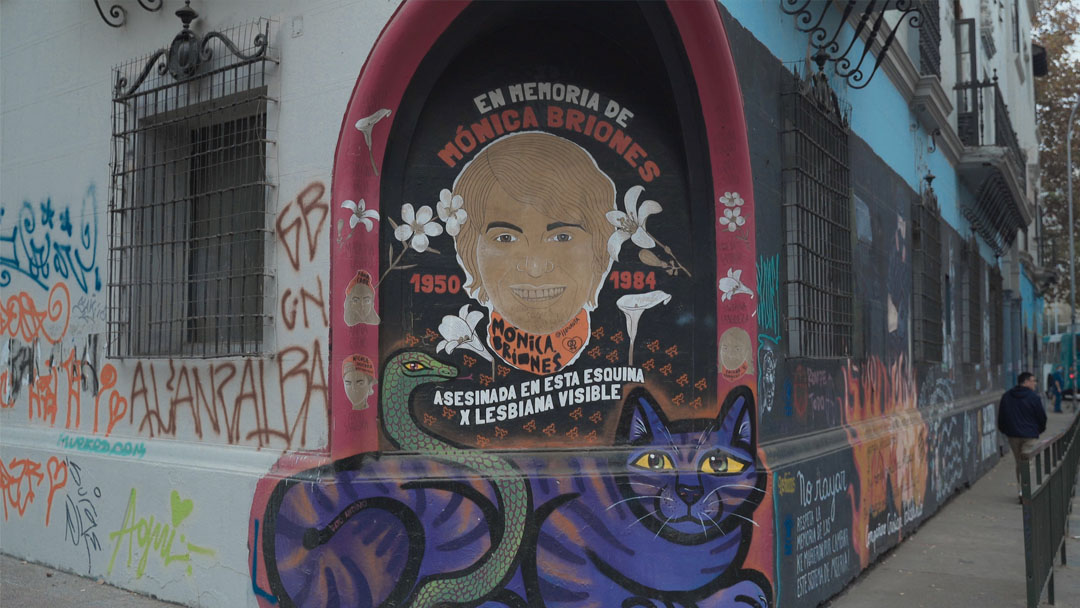

This mural serves as a memorial to Mónica Ángelica Briones Puccio who was a Chilean painter and sculptor during the military dictatorship under Pinochet. On July 9, 1984 she was murdered in the street for being a lesbian. Her murder is considered the first documented lesbophobic crime in Chile. Her death inspired the formation of the Colectiva Lésbica Feminista Ayuquelén, a Chilean LGBT advocacy group. Founded in 1984, Ayuquelén was the sole political voice for LGBT groups in Chile during the mid 1980s and in the period of Pinochet’s dictatorship